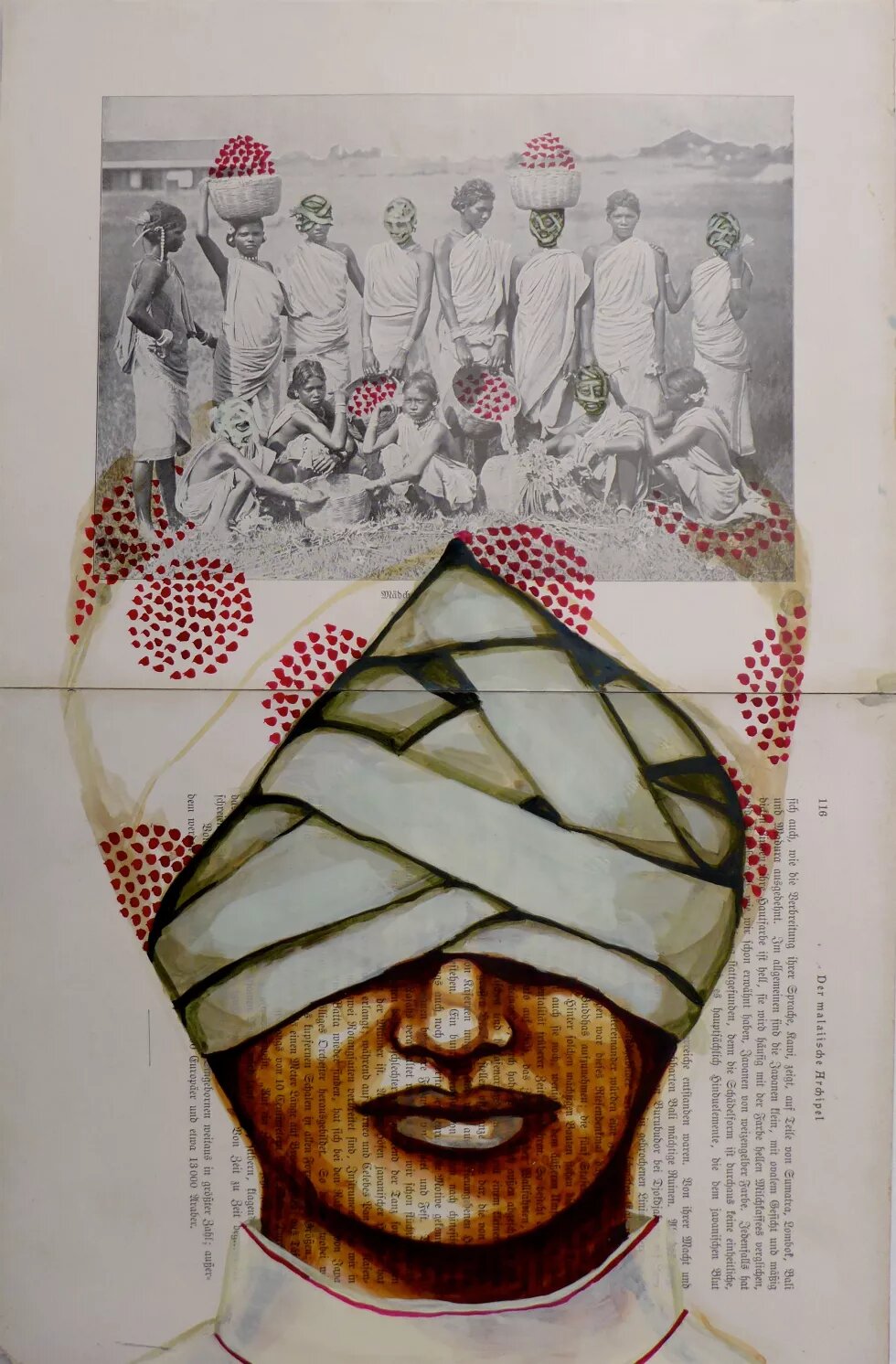

In the work of American artist, Rajkamal Kahlon, an autopsy, a dissection of the visual legacies of empire can be witnessed. The body – injured and transformed – is a reoccurring motif throughout Kahlon’s work. Subject to political and intimate forms of violence, the body also becomes a space for transformation and resistance. Her work remakes the boundaries of political experience into an emotional arena, ranging between anger, grief, revenge and humor.

Kahlon’s interdisciplinary practice questions the formal and conceptual limits of painting, photography and sculpture. Drawing on history, archives and literature, her research undergoes a process of creative transformation. For „We’ve come a long Way to be Together“ (2019), Kahlon painted for example on the top of the pages of a cut-out and reassembled 1st edition copy of the famous travel narrative ‚Arabian Sands‘ and created a series of portraits of travelers from Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

Kahlon’s diverse sources include classical western painting, 19th century illustrated newspapers and history books, contemporary U.S. military autopsy reports, the history of science and medicine, colonial era photography, anthropological portraiture and pop culture.

Vera Heimisch (VH): I saw your exhibition „Are my hands clean?“ at Galerie Wedding, Berlin in 2019 and it made me very curious about you and your ongoing projects. The photographic material of „Die Völker dieser Erde/ People of the Earth“ (2017), which you redrew, illustrates very lucidly the categorization and classification of human beings done by anthropologists and other scholars. But let’s get started slowly. You told me that you often start interviews with giving biographic context. What do we need to know about you in order to understand your work better?

Rajkamal Kahlon (RK): When I give talks I like to begin with some biographical information about myself. I think this is important because it situates the work that I make. I was born in the United States, my parents left Punjab, India, in 1974. In India, they were part of this post-Independence emerging middle class and both work as teachers. When they migrated, my parents were part of a larger wave of immigration to the U.S. targeting the educated classes of the third world. Many doctors, lawyers and teachers entered the fields and factories of the U.S. , where my parents worked as Teamsters in west coast factories. For me, having this working class background and being born and raised in the United States means that I am created out of a history rooted in settler colonialism, genocide and slavery. These founding trauma has rarely been acknowledged in the U.S., and yet are in the soil beneath our feet and part of the air we breathe.

VH: How and when did your artistic path start?

RK: I chose art at a very young age. First I saw it scared my parents, who like many immigrants, hoped I would become a doctor or an engineer.I didn't have any artists and intellectuals in my family. What I had were romantic ideas of what an artist was, which came from television and films. My first art book was a discounted copy on Renoir and impressionism. My parents knew that artists in India come from wealthy and privileged backgrounds which I at the time dismissed as the naive thinking of immigrants.

VH: What happened when you started art school?

RK: I realized once I got to art school that my parents were right (laughs). It is a really hard path to be an artist without family money or some financial backing.

VH: You are negotiating very painful topics through your art work. When did you start to artistically deal with colonialism?

RK: I never saw my work as political until my definition of this category changed. My work is about oppression, inequality and violence. I've spent the last 20 years trying to understand how to represent violence. I started working with colonial history as early as 1997. At this time there was no interest in colonialism. It was a deadly, unfashionable topic. Now, strangely, it has become not only fashionable but also a fundable topic in the art world. When I first arrived in Berlin in 2010 the very same individuals in the art world that were publicly denouncing BPoC artists who worked on colonialism and race, are the very same individuals at the forefront of the discourse on colonialism and funding today. It's really surreal for me to watch this from my perspective as someone committed to critiquing imperial power through the lens of aesthetic justice and liberation for the last 2 decades.

VH: Yes, I totally agree. I have noted many projects working academically and artistically on the impacts of colonialism in Germany at the moment. But you have been dealing artistically more than 20 years with colonialism? What makes it so relevant in your eyes?

RK: Yes – I’ve been working on it my whole life basically. Colonialism is like patriarchy. Colonialism is in everything, and it structures everything. It is a legacy of violence that nobody talks about. In the last few years, there has been some kind of reversal. It's become embedded into a political moment, starting with the so-called migration crisis of 2015. Now suddenly we talk about it and I also wonder if it is going to end and when.

VH: You describe your early stage as an artist as a strategy to survive racism and sexism. What do you mean by that and how did this change in the last years?

RK: I first chose art because it was a survival strategy. It’s a chain of intimate and social/political trauma: my early family life growing up American, being a woman of Color. There were so many layers of trauma put on top of each other. Art was very literally, for many years, just something that helped me survive. It was a cathartic tool that allowed me to speak. Because of the racism and sexism I encountered growing up in the U.S., I just internalized some of it and stopped speaking in school and university. My work is no longer about my own survival. My work has shifted from my own survival to working on the behalf of the men and women that I encounter in colonial archives. My work is made on behalf of vulnerable people and communities that are targeted for destruction. I am trying give voice to, and rehabilitate the traces of the people whose cultures have been destroyed, maligned and erased. What began as survival, I now see as a project of giving voice to those that otherwise wouldn’t have one, those that are the subject and object of violent forms of destruction.

VH: After the many encounters with colonial archives, you understand your work more spiritually: as one of rehabilitation, transformation and restoration of the humanity, dignity and beauty of the people. How do you proceed with the archival material, how do you restore the dignity of the people in the archives?

RK: It's a process. Empathy and embodiment are key to my understanding of working with and in archives. I don’t work with archives as an academic would. Academics have a specific research agenda. I spend a lot of time in archives and I am trying to find meaning that at first I don’t even understand myself. I usually don’t enter the archives with a specific agenda. I'm searching for the proverbial needle in the haystack. The photos or records that will unite years of my research allowing it to suddenly take on an urgent relevance to the present.

In 2016, I was Newhouse Fellow at Wellesley College researching anthropological archives at Harvard for two months. Part of what I encountered was the work of American anthropologist, Henry Fields, who went to Iraq in the 1930s. He measured peoples skulls and their skin color and produced this massive amount of measurement data and also photographs.

I had previously worked on contemporary autopsy reports coming out of Iraq from U.S. military prisons in the project, „Did you kiss the dead body?“ (2008-2012). What struck me was that these documents are about bodies, but there are no declassified images of these bodies. Part of the question behind this work is how do I make present these men who are anonymous and been tortured and murdered?

VH: Would you describe your own approach to the archival materials as very different from that of the archivists or anthropologists who arranged the archive, as you are focusing very much on embodiment and empathy?

RK: Yes, rather than reacting through it through rational lenses I am engaging the material, the people and the traces that I find through an empathic stance. I am trying to stay embodied. When I think about and make work about the men and the women that I find in these photographs or in the measurement data, I am trying to short-circuit the rational and scholastic, academic relationship one has to this kind of data and material.

I am trying to disrupt that. The disrupting comes with these concepts of embodiment and empathy. I’ve been slowly developing this approach, I haven’t made a theoretical discourse about it. Over the years, I find myself doing it intuitively and it means also projecting myself into traumatic history.

VH: Do you understand this disruption as an intervention into archives?

RK: I see it as a disruption that allows new circuits of meaning to take hold and be created from traumatic histories, through objects and within museological institutions.

VH: I imagine it very painful to sift all the archival materials and projecting yourself into it?

RK: Reading the autopsy reports would depress me, it was so ravaging. They are written in cold, clinical medical language. At a point I had to stop working with them. Even going into the archives triggers a huge emotional reaction. But I try not to cut myself off from all of these emotions, I actually make them my starting point.

My anger and my sadness guide me I guess. It hurts, but I know that there is something that needs to be said, because I’m feeling something pulling me closer. It’s about unraveling what that relationship is, mine to the archive and ours collectively to history.

VH: It sounds like you are digging very deep into colonial wounds. How present is the colonial visuality in the ethnographic archival material you work with and how is it connected to violence?

RK: My work is actually made of this intersection of visuality, violence and colonialism. I am thinking through all of these structures. I question myself what happens in this visual discourse. I am looking at violence. How is it located and articulated? How can I intervene instead of reinstate it?

Colonialism is a way to talking about power. I’ve been working on these topics again and again in different ways for two decades.

VH: This seems to be a good moment to come back to your already mentioned work „Die Völker dieser Erde/People of the Earth“ which is an ongoing project that started in 2017. What is it about?

RK: Yes, I started the project during my residency at the Weltkulturen Museum Wien where I purchased a book from an antiquarian book seller in Vienna. „Die Völker der Erde / People of the Earth“ refers to a 1902 German Anthropology book written by Dr. Kurt Lampert. I cut-up the book and use the original pages as a space for „talking back“ to the book, its author, to the discipline of anthropology. Now it exceeds 300 drawings. I think of this work like a giant sketch book. I don't have a precious attachment to one image but rather it is the force of the collective whole, that gives it a kind of monumental power. It's presented like an exploded book.

VH: Thinking about the future of archives: how do you image archives in the future? Do you think we should shut them down, or develop new strategies to archive material?

RK: I appreciate the work of Ariella Azoulay and her work on photography, imperial history and archives. I think the very purpose of the archive which is to name, classify, separate and assign value is inherently violent and disrupts the interconnected flow of life. They are imperial technologies that aid in the targeting and destruction of indigenous, racialized and gendered populations. I think from this point I have always believed I could through my work create aesthetic acts of resistance and poetic rebukes to power.

VH: What are you working on at the moment?

RK: With the pandemic, many of my shows have been postponed and now I am working without immediate deadlines. This is nice. I am finishing the last 100 or so drawings of „Die Völker der Erde“ and finishing the series „Do You Know Our Names?“ before beginning new projects.

Rajkamal Kahlon

For over 2 decades, Rajkamal Kahlon has been extensively researching drawing and painting as sites of political resistance. Her work draws on legacies of colonialism, often using the material culture, documents, and aesthetics of Western colonial archives.

Kahlon's artistic research, which is at the intersection of visuality, violence and colonial histories, has evolved to reflect on how trauma and the body are at the center of colonial violence. Specifically, it is the body in the archive, the one that has been studied and objectified that Kahlon’s work addresses, attempts to rehabilitate, and care for. Kahlon attended the Whitney Independent Study Program and received her MFA from CCA. Her work has been exhibited in museums, foundations and biennials in North America, Europe, the Middle East and Asia. She is the recipient of numerous grants, awards and commissions including the Joan Mitchell Painting and Sculpture Award, Pollock Krasner Award, Stiftung Kunstfonds Arbeitsstipendium, Goethe Institute Künstlerstipendium, American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) National Security Project Artist-in-Residence, Melon Visiting Artist Fellowship, Newhouse Center, Wellesley College, SWICH Artist-in-Residence, Weltmuseum Wien, the 2019 Villa Romana Prize and the 2020 Berlin Artist Grant.